Brief History

Natural & Early History

Like much of Rockport, Andrews Woods sits atop a ledge of 440-million-year-old granite, gently sloping toward the sea. When the last glacier retreated from the area some 15,000 years ago, it left behind only a thin layer of silt, scattered with large “glacial erratics.” Trees struggled to take root, but as leaves began to accumulate, the soil began to turn into the rich, porous loam found on the floor of the woods today.

Like much of Rockport, Andrews Woods sits atop a ledge of 440-million-year-old granite, gently sloping toward the sea. When the last glacier retreated from the area some 15,000 years ago, it left behind only a thin layer of silt, scattered with large “glacial erratics.” Trees struggled to take root, but as leaves began to accumulate, the soil began to turn into the rich, porous loam found on the floor of the woods today.

Each spring, meltwaters recall the glacial retreat as they flow under the woods along the ledge. Summer rains also drain through the woods, percolating to the surface in bubbling streams at its lower (northern) extremities. The abundant water fills depressions, forming pools where wildlife come to drink. The moist soil supports a remarkable variety of mosses and fungi.

Archaeological explorations of the area have found evidence of Indigenous habitation—artifacts, house floors, hearths, a blue quartz quarry on Andrews Point, a corn grinding stone, boulders modified to represent spirit animals, and a burial mound. People were living on the cape at the time of European contact—Algonquians known as the Pawtucket. Despite the rough woods, inhospitable terrain, and exposure to nor’eastern gales, their mixed economy allowed for permanent agricultural settlements as well as summer camps for fishing and clamming, in addition to seasonal migration to inland resources, such as furs and hides for trade. On Cape Ann the people were growing and preserving corn, squash, pumpkins, beans, sunflowers, and tobacco. Each family had a garden and if necessary transported arable soil in baskets to wherever they were camped. Village residents kept communal cornfields. Algonquians had a tradition of pilgrimage and visited Pigeon Cove, Andrews Woods, and other traditional sites on Cape Ann whenever it was safe to do so. Local newspaper accounts describe their visits through the 1880s.

The Indigenous people also practiced silviculture, protecting preferred trees in managed groves surrounded by open parkland, which they created and maintained through controlled burns. The earliest accounts of European explorers describe the northern tip of Cape Ann as the “forest primeval.” Tree species included a mixture of softwoods, such as spruce, fir, cedar, and white pine, and hardwoods, such as rock maple, oak, ash, elm, chestnut, sycamore, hickory, aspen, black birch, and basswood. The timber was, apparently, far superior to what was found just off the Cape, as was well known to the builders of Salem and Boston. Today, some of these species remain, and some have disappeared. Present-day tree species include oak, flowering shad, black cherry, and pitch pine. Among the shrubs and other plants in the woods are anemone, trillium, low-bush blueberries, blackberries, huckleberries, pink lady slippers, winterberry, Solomon’s seal, and Canadian mayflower.

1600s

European settlement of Cape Ann began at the turn of the 17th century, and the area around Andrews Woods was quickly identified as an important woodland resource. Timber was the first English colonial export. The “Cape Forest” was owned in common by the townspeople of Gloucester (of which Rockport was a part until 1840), and early town meetings put restrictions on removal of the timber. Despite the potential for sales to construction and shipbuilding interests, and persistent pressures for development, the restrictions continued in some form throughout the 17th century.

The first recorded regulation was in 1642. A fine of 10 shillings was placed on any timber removed from the woods without permission. Three years later, the penalty was increased, so that “whoever hee bee that shall from this date forward cutt downe anie Tymber trees without leave shall paie the value of 10s per tree.” Hoop poles—the flexible saplings that replaced felled trees, much valued for barrel hoops, and for which the adjacent cove is named—were explicitly included in the regulation. By 1650, townspeople were allowed to timber 20 cords per family per year, but the permits required a specified place, time, and quantity.

In 1667, town meeting relented to the pressures for timbering and development. The woods had become “too valuable” to leave alone. Cutting was allowed up to 660 ft back from the shore, from Brace Cove in East Gloucester around the cape to Plum Cove in Lanesville, and active clearing commenced almost immediately. The competition for the timber became so fierce that town meeting first passed a regulation fixing prices, and then, as the supply neared exhaustion in 1670, voted to preserve selected trees marked with an X, so that they could bear acorns for future growth. In time, through deforestation and overgrazing, Andrews Woods, like Dogtown, became a treeless glacial heath reminiscent of earlier geologic times.

In 1667, town meeting relented to the pressures for timbering and development. The woods had become “too valuable” to leave alone. Cutting was allowed up to 660 ft back from the shore, from Brace Cove in East Gloucester around the cape to Plum Cove in Lanesville, and active clearing commenced almost immediately. The competition for the timber became so fierce that town meeting first passed a regulation fixing prices, and then, as the supply neared exhaustion in 1670, voted to preserve selected trees marked with an X, so that they could bear acorns for future growth. In time, through deforestation and overgrazing, Andrews Woods, like Dogtown, became a treeless glacial heath reminiscent of earlier geologic times.

In 1688, town meeting laid out 6-acre parcels around the cape and made them available to all males over the age of 20. By 1700, settlers with the new land grants had moved into the area, and most of the remainder of the common woods was cleared. The 1647 Massachusetts Bay Colony Ordinances had moved coastal property lines down to the low water mark, setting up centuries of contention regarding public access to the shoreline.

1700s

Through the 1700s, the settlements at Sandy Bay (which would become the center of Rockport) and Pigeon Cove to the north increased slowly in population. Farming, woodcoasting (shipping hoop poles, firewood, and other timber) and shore fishing were the chief occupations. The harbors and coves in the area were too small and too exposed to the sea to develop the offshore fishing and foreign trade that thrived in Gloucester and Salem.

The first settler to establish a farm in the area around Andrews Woods was Samuel Gott, who built a house just to the north sometime around 1700. Besides his lots on Halibut Point, Gott also owned lots around Hoop Pole Cove. He sold these to his brother-in-law William Andrews in 1702, including the areas that are now known as Andrews Point, Andrews Hollow, and Andrews Woods. Andrews Woods was once William Andrews' orchard. The rock walls that still run through the woods appear on later maps, marking "Andrews' Pasture," though their exact date of origin is unclear.

Gott and Andrews Farms.

Modern roads and Andrews Woods (green) superimposed.

Andrews family heirs continued to live in the area through the late 1770s. After that time, lots were sold to various neighbors, and continued to be used for farms and pasture land.

1800s

The hoop pole industry, begun in the 1600s, continued to thrive through the 1800s. Hoop poles came to be widely used not only for barrels, but also as stiffeners in fashionable women's hoop skirts. (Hoop poling is described in in this 1893 article from the New York Times.) As some of the older pastures around Andrews Woods began to grow over, it is likely that the area continued to be scavenged for hoop poles and quick cash.

The hoop pole industry, begun in the 1600s, continued to thrive through the 1800s. Hoop poles came to be widely used not only for barrels, but also as stiffeners in fashionable women's hoop skirts. (Hoop poling is described in in this 1893 article from the New York Times.) As some of the older pastures around Andrews Woods began to grow over, it is likely that the area continued to be scavenged for hoop poles and quick cash.

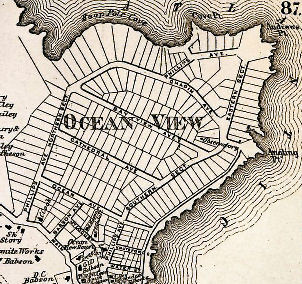

Such bucolic pursuits did not last, however. By mid-century, Eben Phillips, the "fish oil king" of Swampscott, was busy mapping out grander plans for the area. Phillips bought up the pastures and woodlands in the northern end of Pigeon Cove in 1855, speculating on the extension of the railroad from Gloucester to Rockport. He kept buying until he owned virtually all of the land around Andrews and Halibut Points. Around 1870 Phillips launched his plan for "Ocean View," a summer resort that divided the area into over 200 buildable lots, encircled by the wide, mile-long Phillips Avenue. (See Historical Maps.)

Such bucolic pursuits did not last, however. By mid-century, Eben Phillips, the "fish oil king" of Swampscott, was busy mapping out grander plans for the area. Phillips bought up the pastures and woodlands in the northern end of Pigeon Cove in 1855, speculating on the extension of the railroad from Gloucester to Rockport. He kept buying until he owned virtually all of the land around Andrews and Halibut Points. Around 1870 Phillips launched his plan for "Ocean View," a summer resort that divided the area into over 200 buildable lots, encircled by the wide, mile-long Phillips Avenue. (See Historical Maps.)

Phillips built the Ocean View House in 1871 as an anchor hotel at the southern end of his development and sold a few lots along the shore. (See Historical Photos.) He was planning a much larger hotel at the end of Andrews Point when he died in 1879. The land around Andrews Woods was deeded to his wife, Maria Phillips, but she and her heirs sold off lots at a much less ambitious pace. Andrews Woods, just back from shore views and burdened by its shallow, septic-unfriendly granite ledge, was spared.

Pigeon Cove continued to be a popular summer destination through the end of the century, as small boarding houses gave way to large hotels and later to mansions along the coast.

Point de Chene Ave and the Linwood Hotel, late 1800s.

Modern History

The collapse of the local granite industry following the stock market crash of 1929 finally ended Pigeon Cove's status as a resort community. The Great Depression of the 1930s, however, brought renewed interest in acquiring land around Andrews Woods for conservation purposes. At the beginning of the 30s, 17 acres on the eastern side of the Babson Farm quarry on Halibut Point were purchased from the Rockport Granite Company and given to the Trustees of Reservations. In 1934, with funds from Rockport residents and Dr. John Phillips, the Trustees acquired land connecting the Halibut Point reservation to the western edge of Andrews Woods. The land sat mostly unused until late in World War II, when Halibut Point became the site of a coastal defense tower. It was sometime shortly after the war that the Trustees, for reasons that are unclear, sold off the property between their current reservation and Andrews Woods, isolating the woods from the conservation areas just 1/4 mile to the north.

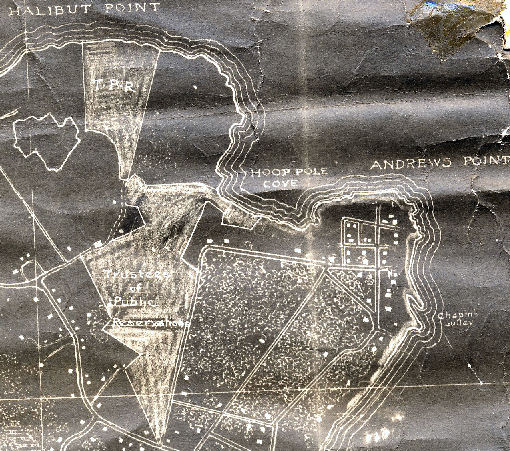

1944 map showing former Trustees of Reservations

land connecting Andrews Woods to Halibut Point.

The 1970s saw sewer lines introduced to the area and rapid development throughout Pigeon Cove. One local real estate agent recalls "driving around the neighborhood and licking our chops." Others refer to the time as one of "sewercide," when much of the remaining open space in the neighborhood—with Andrews Woods one of the few exceptions—disappeared.

The 54-acre Halibut Point State Park was established in 1981 adjacent to the remaining Trustees of Reservation land. In May 1987, the Rockport Select Board created an ad hoc committee to clarify ownership of rights of way belonging to the town and to ensure that they be kept open to public passage. The Rockport Rights of Way Committee was permanently established by a vote of town meeting in March of 1989, and continues to maintain, with the help of neighborhood residents, the trails in Andrews Woods and along the Atlantic Path. In 1991, Massachusetts passed a special act allowing free right-of-passage to public foot traffic between the low and high tide line, finally reversing key provisions of the 1647 ordinance and helping to re-establish connections between Andrews Woods and shoreline paths.

Today, Andrews Woods is the acknowledged "Central Park" of Pigeon Cove, central not only to neighborhood recreation, but also a central link in the chain of trails that connects Halibut Point to the north and the Atlantic Path to the south. A recent history of neighborhood caretaking is demonstrated each Earth Day with an annual event to clean up the woods and maintain the trails.